Lab 2: Bluetooth Communication

This lab was dedicated to establishing a wireless connection from my personal laptop to the Artemis Nano via the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) protocol.

The main objective in doing so is to setup an efficient way to monitor and debug the sensors and actuators of the robot, and to allow for computational offloading of control actions.

Setup:

To start off, I created a Python virtual environment dedicated to installing and running python packages related to the BLE protocol:

pip install numpy pyyaml colorama nest_asyncio bleak jupyterlab

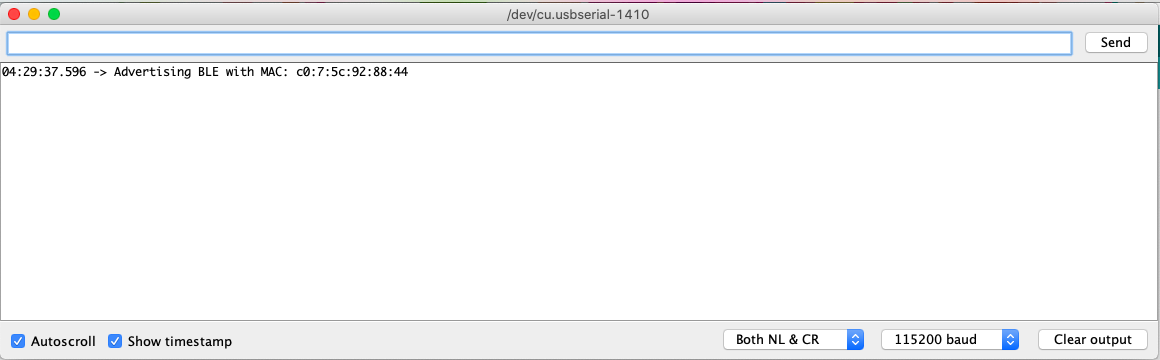

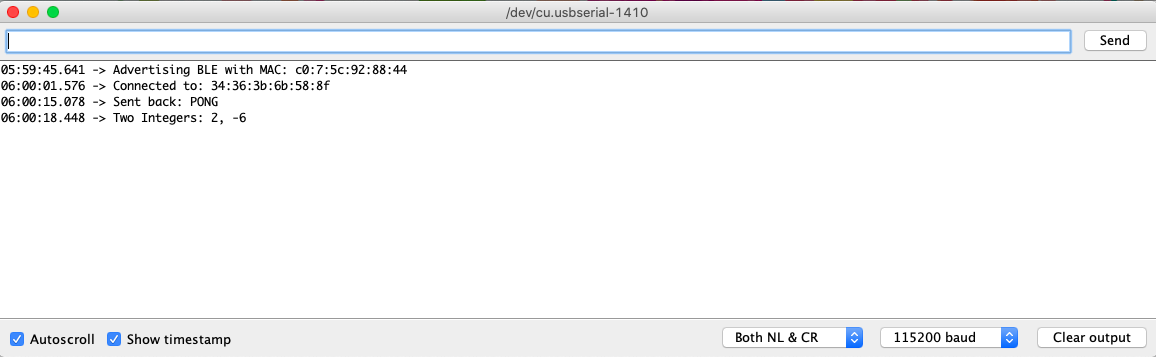

After setting up this on my laptop, I then used the ArduinoBLE library to establish a simple connection to the Artemis Nano that recorded the MAC address of the board:

Combined with a newly generated UUID, I recorded this information on both my personal computer and the Artemis Nano so that both devices would be guaranteed to establish a shared connection.

The connection was then tested via importing the ble package in a Jupyter notebook, followed by simply instantiating a controller object and connecting:

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload 2

from ble import get_ble_controller

from base_ble import LOG

from cmd_types import CMD

import time

import numpy as np

LOG.propagate = False

# Get ArtemisBLEController object

ble = get_ble_controller()

# Connect to the Artemis Device

ble.connect()

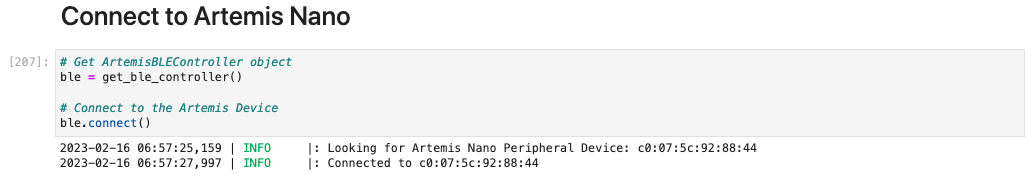

The successful connection can then be observed below:

Codebase:

In short, the Bluetooth protocol mainly consists of peripheral devices such as the Artemis Nano that advertise services, each of which contain various characteristics that hold 512 byte values. To identify a particular service or characteristic, the protocol uses a specific bit string known as a Universal Unique Identifier (UUID).

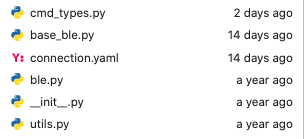

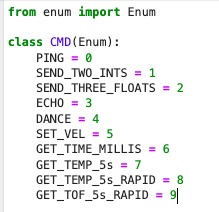

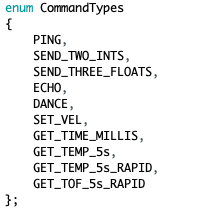

The code necessary to establish the Bluetooth connection contained quite a lot of different parts, both for the laptop and on the Artemis Nano. The laptop files included a connections.yaml file for recording the MAC address and a service UUID to connect to the Artemis Nano with, as well as characteristic UUIDs for receiving and transmitting data. A second file, cmd_types.py, contained a Python enum datastructure for storing specific Bluetooth command names listed by number.

Besides these simpler accessory files, the Python code responsible for doing the heavy lifting was left to ble_base.py and ble.py, which are modules that setup the groundwork to build a user-friendly BLEController class that can easily connect/disconnect and send/receive data. Most importantly, the class also offers the freedom to write notification handlers that will be called whenever the computer receives data through a particular characteristic UUID, which helps facilitate asynchronous data collection. Finally, a couple other printing and logging features are left in a utils.py script to better record and organize events that occur while using the Bluetooth connection.

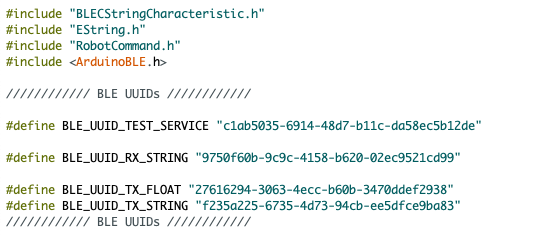

A somewhat similar code setup is also burned onto the Artemis Nano, which consists of a ble_arduino.ino file recording the UUIDs and enumerated command types, as well as a command handler executed with a specific response to each command. This script is also used to advertise the Bluetooth service, setup the relevant characteristics, and read out the MAC address of the Artemis Nano.

A few other header files including BLECStringCharacteristic.h, EString.h, and RobotCommand.h define classes that are used to handle the characteristic data in cases that are not covered by the ArduinoBLE library. In particular, the BLECStringCharacterstic.h and RobotCommand files are dedicated specifically for formatting and parsing string characterstics and robot commands, whereas EString.h mainly just holds a bunch of helper functions to make string manipulation (technically on character arrays) a bit easier.

Configurations:

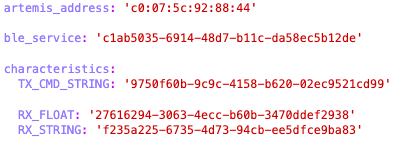

As mentioned before, the first step in establishing the Bluetooth connection was to ensure that the configurations were consistent across both devices. This included the UUIDs and command types:

Admittedly, the list of command types was a bit longer than necessary, which was mainly to prepare for the rest of the lab and future labs.

Demo:

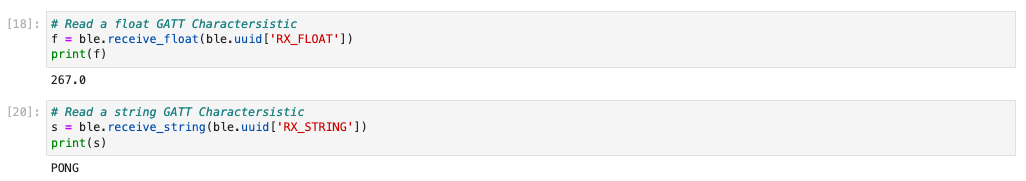

The next step was to run a simple demo of basic Bluetooth commands, which mainly consisted of sending and receiving strings, integers, and floating point values::

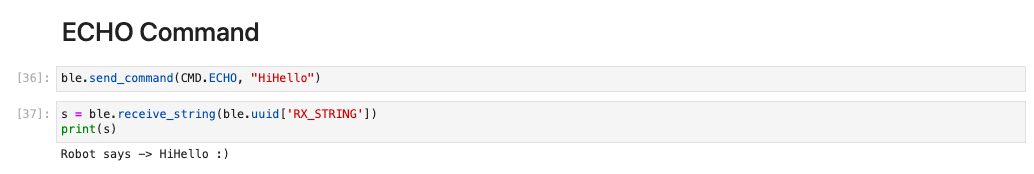

Echo Command:

The first lab task was to send an ECHO command, which basically involved modifying the string characteristic value on the side of the Artemis Nano and then simply returning the modified string back to the computer:

case ECHO:

char char_arr[MAX_MSG_SIZE];

// Extract the next value from the command string as a character array

success = robot_cmd.get_next_value(char_arr);

if (!success)

return;

// Write augmented string back

tx_estring_value.clear();

tx_estring_value.append("Robot says -> ");

tx_estring_value.append(char_arr);

tx_estring_value.append(" :)");

tx_characteristic_string.writeValue(tx_estring_value.c_str());

break;

Get Time Command:

The next command was GET_TIME_MILLIS, which simply returned a timestamp at the moment of receiving the command:

case GET_TIME_MILLIS:

// Write string back

tx_estring_value.clear();

tx_estring_value.append("T:");

tx_estring_value.append(int(millis()));

tx_characteristic_string.writeValue(tx_estring_value.c_str());

break;

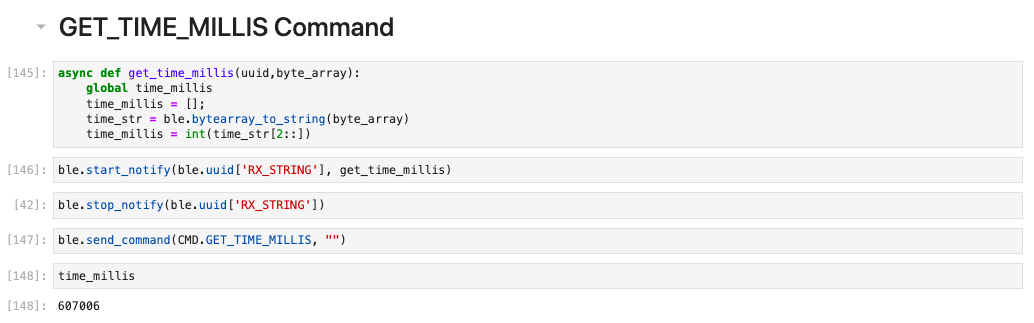

Setting up a Notification Handler:

To make things a little more interesting, a simple notification handler function was added, which just extracted the time in milliseconds out of the string:

async def get_time_millis(uuid,byte_array):

global time_millis

time_millis = [];

time_str = ble.bytearray_to_string(byte_array)

time_millis = int(time_str[2::])

Get Temperature Command:

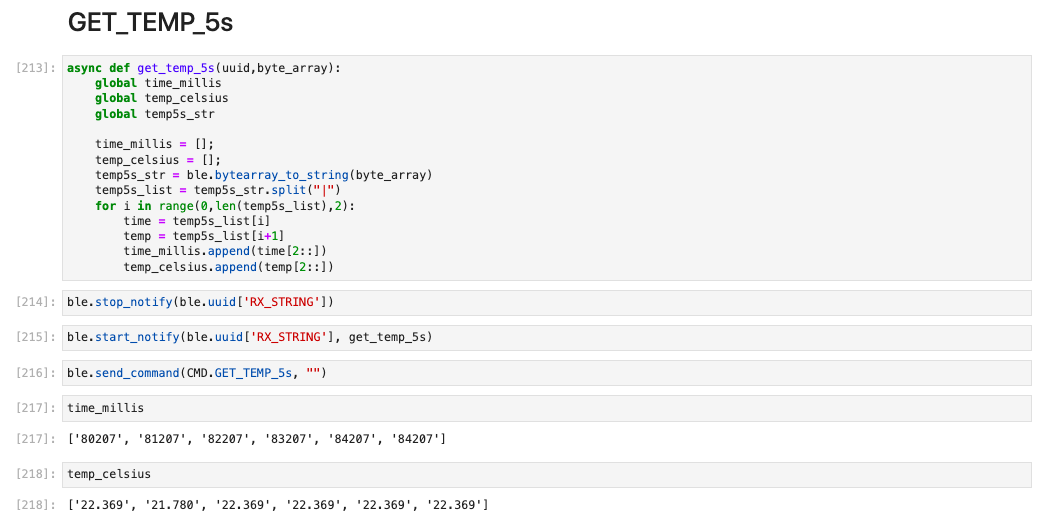

Building off of the previous command, GET_TEMP_5s was made to send a set of timestamped die temperatures sampled once per second over a five second period was sent.

case GET_TEMP_5s:

int prev;

int count;

int current;

// Write string back

tx_estring_value.clear();

prev = millis();

count = 0;

while(count < 5){

current = millis();

if (current - prev >= 1000){

tx_estring_value.append("T:");

tx_estring_value.append(int(millis()));

tx_estring_value.append("|C:");

tx_estring_value.append(getTempDegC());

tx_estring_value.append("|");

prev = current;

count++;

}

}

tx_estring_value.append("T:");

tx_estring_value.append(int(millis()));

tx_estring_value.append("|C:");

tx_estring_value.append(getTempDegC());

tx_characteristic_string.writeValue(tx_estring_value.c_str());

break;

The following notification handler essentially partitioned the strings based off of the separating delimiter “|”, and arranged the corresponding timestamps sand temperature readings into their respective lists:

async def get_temp_5s(uuid,byte_array):

global time_millis

global temp_celsius

time_millis = [];

temp_celsius = [];

temp5s_str = ble.bytearray_to_string(byte_array)

temp5s_list = temp5s_str.split("|")

for i in range(0,len(temp5s_list),2):

time = temp5s_list[i]

temp = temp5s_list[i+1]

time_millis.append(time[2::])

temp_celsius.append(temp[2::])

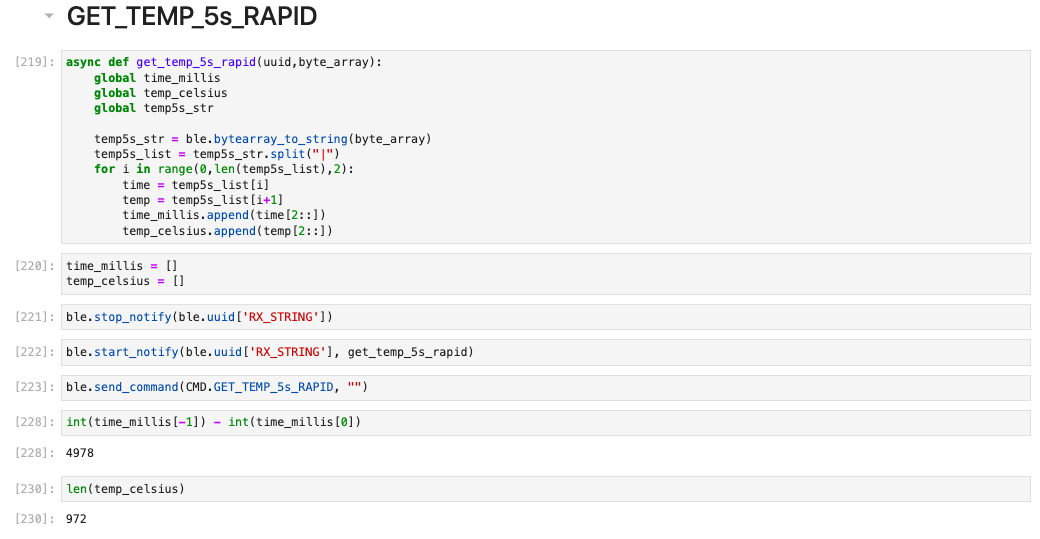

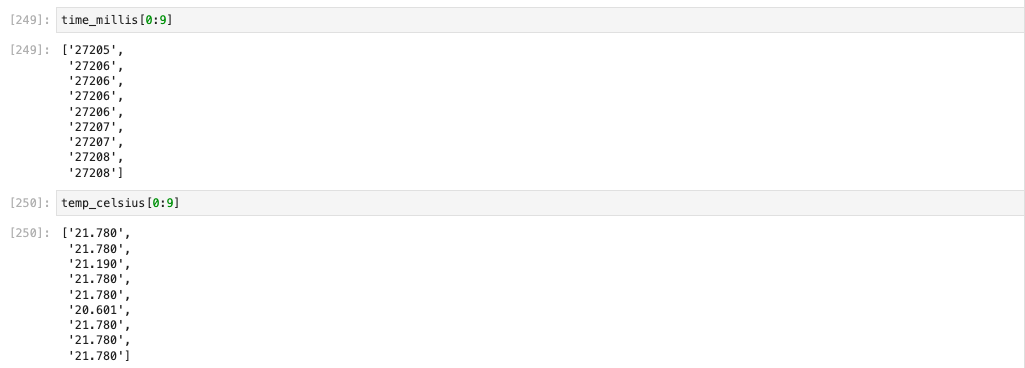

The next command, GET_TEMP_5s_RAPID, then put the sampling and communication rate to the test by sending rapidly sampled timestamped temperatures over a period of five seconds. To ensure that the string did not exceed the maximum byte size limit of 150 (151 including the null terminal character), the characteristic string value was periodically sent out and cleared to avoid indexing outside of the character array size and to avoid using up too much onboard RAM.

Note that since characters are encoded via ASCII, each char value only takes up 1 byte of space. Hence, the length of the string essentially dictates the byte size of the characteristic value, which is used to check that the string meets the size constraints. This is demonstrated below:

case GET_TEMP_5s_RAPID:

int rapid_prev;

int rapid_count;

// Write string back

tx_estring_value.clear();

rapid_prev = millis();

rapid_count = 0;

while(millis() - rapid_prev < 5000){

tx_estring_value.append("T:");

tx_estring_value.append(int(millis()));

tx_estring_value.append("|C:");

tx_estring_value.append(getTempDegC());

if (rapid_count >= 5 || tx_estring_value.get_length() >= MAX_MSG_SIZE - 50 ) {

rapid_count = 0;

tx_characteristic_string.writeValue(tx_estring_value.c_str());

tx_estring_value.clear();

}

else {

tx_estring_value.append("|");

rapid_count++;

}

}

tx_estring_value.clear();

break;

The corresponding notification handler in Python simply took the same strategy as before with GET_TEMP_5s, but the key difference was that the lists of values were continually appended until the five second time interval has ended.

async def get_temp_5s_rapid(uuid,byte_array):

global time_millis

global temp_celsius

temp5s_str = ble.bytearray_to_string(byte_array)

temp5s_list = temp5s_str.split("|")

for i in range(0,len(temp5s_list),2):

time = temp5s_list[i]

temp = temp5s_list[i+1]

time_millis.append(time[2::])

temp_celsius.append(temp[2::])

This successfully resulted in nearly a thousand recorded values, as shown below:

Limitations:

Although communicating over Bluetooth has proven to be great at real-time communication, it is important to note that the rate is limited by how often the Artemis board can update the characteristic values rather than how fast it takes to send the data once the characteristics have been updated.

This is actually a pretty significant issue, since a substantial proportion of the processing power of the Artemis board will not be dedicated to communication, as it will be needed to properly localize and control the robot. We would therefore require data to sit in memory and get flushed out in chunks to the computer rather than send data all the time. Thankfully, the Artemis board has a substantial amount of RAM of 384 kB, but this too will eventually run out over a long enough period of time.

To provide some example estimates of the limitations of the Artemis board’s memory, a table of the maximum storage times for various C++ datatypes on the Artemis Nano is given, assuming that data is generated at a frequency of 150 Hz.

| Byte Count | C++ Datatypes (32-bit processor) | Maximum Storage Time (s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | char | 2621.44 |

| 2 | short | 1310.72 |

| 4 | single-precision float, int, long | 655.36 |

| 8 | double-precision float | 296.96 |

Of course, sampling at even higher rates will result in even more limited storage times than what is shown in the table. However, given that most motors operate at a control loop bandwidth in the hundreds of Hz range, these estimates at 150 Hz should give a more or less accurate order of magnitude guess for the maximum storage limit of different datatypes.

Since most sensor measurements are stored in either float or integer values, we would need to continually send values once every 10 minutess (or possibly faster) to ensure that the Artemis board does not run into any fatal memory issues.